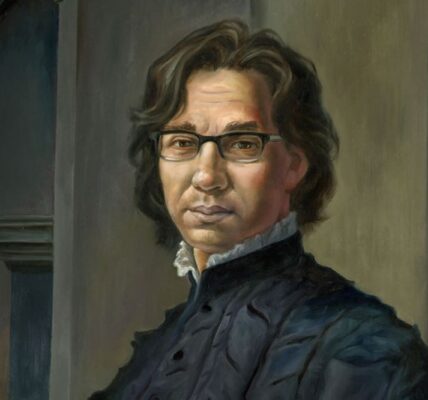

The Godfather of Hypercapitalist Rebellion: Rothbard, the Market, and the Illusion of Liberation

I first encountered Murray Rothbard the way you stumble across a bad idea dressed up as brilliance: through an overconfident college libertarian insisting that taxation was theft and democracy a scam. We were in a political theory seminar. The guy, an engineering major with full red-pill energy, started quoting some economist I’d never heard of who, apparently, had “predicted everything.” He said the state was just a gang of thieves. He said consent wasn’t real unless you could opt out. It sounded like a Silicon Valley fever dream with citations.

I jotted the name down and later found one of his books in the campus library. For a New Liberty—thin, smug, like a pamphlet in a suit. Austrian school economist. Hardcore libertarian. Called himself an anarcho-capitalist. It felt like stumbling into the rough draft of every crypto-libertarian think piece I didn’t yet know I’d be forced to read. I found his ideas silly at first. Then unsettling.

The deeper I went, the more it became clear. Rothbard wasn’t just a fringe economist. He was an architect. A system-builder. And if you trace enough of the DNA behind today’s anti-democratic, market-fundamentalist, racially coded techno-authoritarianism, you find Rothbard in the bones.

He’s not on syllabi. You won’t find him on T-shirts. But his presence lingers in the ideology of a new elite who believe markets should rule everything, states are the enemy, and any regulation is a moral offense. Rothbard’s project wasn’t just anti-government. It was anti-egalitarian, anti-democratic, and deeply committed to a vision of liberty where the strong rule, the rich inherit, and the poor are simply unfortunate.

And he did it with a smile. With jokes. With charisma. That’s what makes him dangerous.

Rothbard was born in the Bronx in 1926, into a Jewish family surrounded by Communist sympathizers. According to his biographer, Justin Raimondo, Rothbard grew up rebelling against the dominant leftism of his community and household. The exception was his father, who was a pro-capitalist individualist. It’s tempting to read his life as one long overcorrection, a swing from the overbearing collectivism of his upbringing to the gospel of absolute individual sovereignty.

But that would be too psychological. Rothbard wasn’t merely reacting. He was constructing. By the 1950s, he was a full-throated apostle of Ludwig von Mises and the Austrian school of economics. But unlike Mises, Rothbard didn’t just want to critique state intervention. He wanted to delegitimize the state entirely. Not shrink it. Not balance it. Abolish it.

He coined the term “anarcho-capitalism,” the belief that markets can do everything better than governments and that all forms of collective governance are inherently coercive. In Rothbard’s world, justice should be privatized. Roads, courts, security, all of it. If there was a problem with society, it was because the government had touched it.

But what made Rothbard more than just a free-market fundamentalist was his gleeful extremism. He wasn’t dry like Hayek or formal like Friedman. Rothbard had the soul of a provocateur. He compared taxation to slavery. He called the state a “criminal gang.” He opposed civil rights laws, not out of racism, he claimed, but because they infringed on property rights. In Rothbard’s moral universe, the freedom to discriminate was sacred—because it was yours.

That’s not libertarianism. That’s license as hierarchy. It’s the freedom of the powerful to dominate without interference.

Reading An Enemy of the State, you begin to see how Rothbard moved from radical economic theory into something darker. Raimondo is uncritical. He treats Rothbard like a folk hero. But the biography lays bare something its author doesn’t seem to notice. Rothbard’s intellectual journey is less about liberty and more about the pursuit of ideological purity, even when it meant alliances with the far right.

In the 1960s, Rothbard briefly flirted with the New Left. He opposed the Vietnam War and saw student radicals as fellow enemies of the state. But the honeymoon didn’t last. When the counterculture moved toward egalitarianism and identity politics, Rothbard turned away. What he really wanted wasn’t revolution. It was rejection—of the state, of redistribution, of collective responsibility.

In the 1990s, Rothbard allied himself with Pat Buchanan’s “paleoconservatism” and even praised David Duke’s political campaign, justifying it as a populist backlash against the “elites.” Rothbard’s supposed anarchism didn’t stop him from admiring authoritarians, so long as they claimed to fight “statist egalitarianism.” In one essay, he described Duke’s platform as “sound” and dismissed the candidate’s Klan past as irrelevant. His commitment to liberty proved flexible when whiteness and hierarchy were at stake.

That wasn’t accidental. Rothbard’s libertarianism was always structured around property rights as the core moral unit. But in practice, this meant defending the power of the wealthy and dismissing any structural critique of inequality as an attack on “freedom.” That’s why he opposed the Civil Rights Act, defended housing discrimination, and considered democracy a threat to liberty. Majoritarian rule might vote to limit your “right” to exclude, exploit, or hoard.

He built a moral system where wealth was virtue, power was earned, and the social contract was theft.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is. Rothbard’s ideas have quietly infused the worldview of some of today’s most influential thinkers and funders.

Peter Thiel, who once wrote that freedom and democracy are incompatible, cites Austrian economics as formative. Curtis Yarvin, a direct Rothbard disciple, turned that philosophy into a blueprint for post-democratic techno-monarchy. Ron Paul’s newsletters in the 1990s echoed Rothbardian talking points, often spiked with barely veiled racism. The cryptocurrency world, obsessed with exit, autonomy, and the gold standard, is deeply Rothbardian in tone, if not always in theory.

And Rothbard’s fingerprints are all over the “anti-woke” movement, which frames social justice as tyranny and market freedom as moral salvation. When today’s tech elite complain about regulation as “coercion” and universities as “cathedrals of control,” they are channeling Rothbard, even if they’ve never read him.

But the real danger isn’t the policy. It’s the permission structure. Rothbard’s legacy gives the powerful a moral story for their power. A story where redistribution is theft, regulation is violence, and any challenge to capital is an existential threat to liberty. It allows billionaires to see themselves not as oligarchs, but as liberators. Martyrs of the market.

Of course, Rothbard’s defenders say he was simply consistent. That he followed the non-aggression principle to its logical conclusion. That he opposed war, the draft, and corporate welfare. And to a point, that’s true.

But consistency without humanity is a brittle virtue. Rothbard could write entire treatises on property rights without ever confronting the realities of race, class, or power. He could rail against the state for violating rights while saying nothing about how capital concentrates power and produces dependency. In his world, everything unjust happens through government. Everything else is just “voluntary.”

It’s a neat trick. One that allows exploitation to vanish behind the language of consent. If you’re underpaid, it’s because you agreed to it. If you’re evicted, it’s because you signed a lease. If you’re excluded from opportunity, it’s because someone else had the freedom to deny it to you.

That’s not liberty. That’s a smokescreen.

The truth is, Rothbard’s vision of freedom was never meant for everyone. It was built for a world where people are atomized, competition is sacred, and hierarchy is natural. It’s a worldview that sees solidarity as coercion, justice as theft, and the public good as a trap.

And yet, he succeeded. Not by making his name mainstream, but by laundering his ideology through institutions, think tanks, newsletters, and movements. The Koch brothers funded it. The Ron Paul Revolution amplified it. And today, Silicon Valley elites live inside its echo chamber, dreaming of network states, sovereign individuals, and freedom from the obligations of democracy.

Strip away the branding, and what’s left is a deeply cynical, deeply hierarchical politics. One where freedom means the strong prevail. One where the market is god, and the rest of us are offerings.

I started reading Rothbard because some guy in class wouldn’t shut up about him. I kept reading because I needed to understand why so many of the world’s winners think they’ve been wronged. Why billionaires tweet about “liberty” while crushing unions. Why crypto libertarians rage against the Fed but ignore child poverty. Why the people who benefit most from society believe they’re its greatest victims.

And I think I get it now.

Rothbard gave them a story. One where they’re not hoarding power, they’re protecting freedom. One where they’re not rigging the game, they’re playing by the only rules that matter. One where democracy isn’t messy, fragile, and necessary—it’s obsolete.

And for that story to work, they need us to believe it too.

We shouldn’t.