It started, as these things often do, on a forum.

I was reading a thread about why democracy was failing: some long, snarky manifesto that blended tech optimism with weird medieval nostalgia. Someone was waxing poetic about Singapore as a model of governance, quoting Moldbug like scripture. The tone was arrogant and oddly hypnotic. The content? Authoritarianism dressed in startup language.

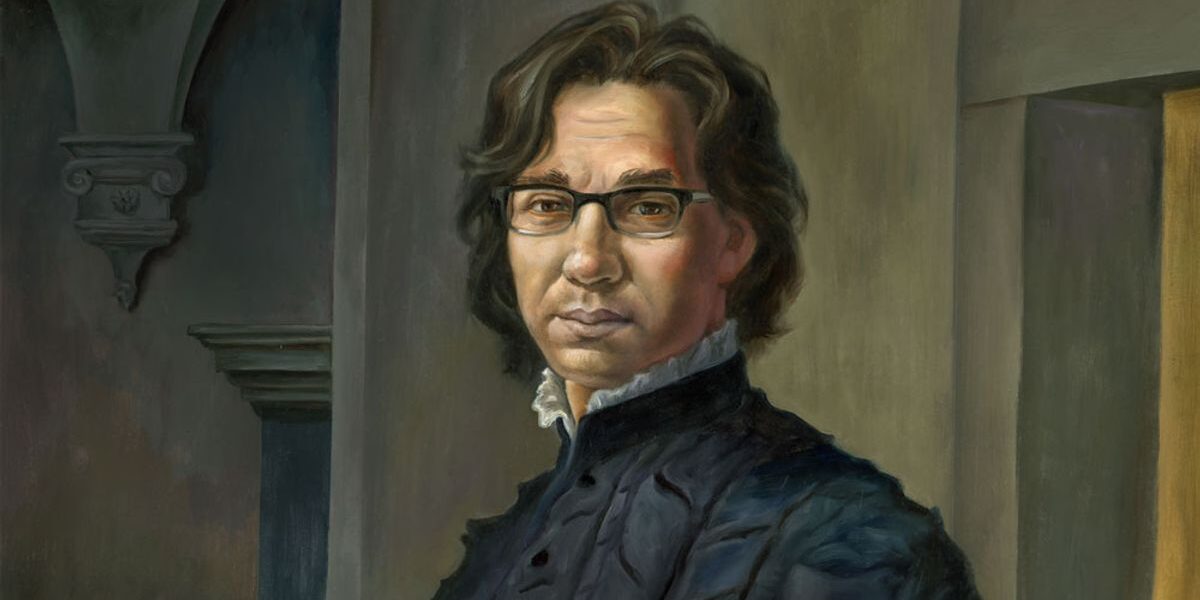

I didn’t know who Moldbug was. But the name kept coming up, half-joke, half-gospel, on Reddit, in early Substacks, in Twitter replies under Peter Thiel’s orbit. So I did the usual thing: typed “Curtis Yarvin” into Google and fell down a rabbit hole lined with footnotes, blog posts, and manifestos that read like they were written by a monarchist who just discovered GitHub.

It was all there: the blog Unqualified Reservations, the idea that the United States should be ruled by a “CEO” rather than a president, the claim that democracy is a failed experiment, and, oh yeah, his flirtations with race science and monarchy. At first, I brushed it off as another fringe libertarian with a God complex. I’d grown up around people who quoted Ayn Rand and owned gold bars “just in case.” This felt like the same kind of guy, just with more tech-savvy prose and a flair for the obscure.

But then I kept seeing his fingerprints in places they didn’t belong. In tech bros talking about “exit” instead of reform. In Peter Thiel’s call for “startup cities” and “functional monarchies.” In the anti-democratic undercurrent that suddenly had elite backing, not just Reddit kids but billionaires and senators.

That’s when it stopped being a curiosity. It started to feel like a warning.

Curtis Yarvin, for the uninitiated, is the intellectual architect behind what he calls “neoreaction” or “NRx.” He writes long, meandering essays that mix programming metaphors with 19th-century political theory, all building up to one idea: democracy is broken, and what we need is an “enlightened despot,” a sovereign CEO to run society like a corporation.

What sounds like satire is, in fact, quite serious.

Yarvin’s argument is that modern states are inefficient, bloated, and hijacked by what he calls “the Cathedral,” a decentralized network of media, academia, and bureaucracy that allegedly enforces progressive orthodoxy. In his model, liberal democracy is not freedom. It’s a soft dictatorship in denial.

The solution? Replace it with a new kind of monarchy. Not inherited kings, but technocratic executives — men of vision and will. Elon Musk types. Peter Thiel types. You see where this is going.

In the early days, Yarvin’s ideas were dismissed as niche blogosphere ramblings. But over time, something shifted. The fringe became the pipeline. Ideas that once lived in the back alleys of obscure forums began to creep into mainstream conversations: about “governance,” “order,” and “civilizational collapse.”

Peter Thiel, billionaire co-founder of PayPal and early Facebook investor, reportedly read Yarvin’s blog and found it “interesting.” Thiel funded institutions like the Heterodox Academy and the Journal of Political Philosophy that pushed similarly anti-democratic ideas under the banner of “heterodoxy.” And more than once, Yarvin has appeared in interviews with venture capitalists and intellectual dark web figures, speaking freely about why America needs a “shutdown” and a reboot under a centralized sovereign.

But what really crystallized Yarvin’s danger for me wasn’t the theory. It was the tone. The calm, reasoned cadence. The appeal to systems. The idea that this wasn’t about ideology, but “efficiency.” That if we just “refactored” the code of governance, we could optimize civilization.

It’s a slippery little trick: turn politics into engineering, people into variables, and freedom into a bug to be debugged.

What makes Yarvin more dangerous than your average internet contrarian isn’t just his ideas. It’s how he wraps them in aesthetics that appeal to a certain kind of disillusioned man. Usually young, white, college-educated, and swimming in libertarian forums. They start off rejecting identity politics. Then they start questioning democracy. Then they find Moldbug.

And what they find is seductive: a universe where everything makes sense. Where disorder is the result of “leftist rot” and “egalitarian myths.” Where hierarchy is natural and good. Where the Founding Fathers went too soft, and the Civil War was a mistake. Where people aren’t equal — not because of injustice, but because they were never meant to be.

Yarvin doesn’t shout these ideas. He seduces you with them. He buries them under 10,000 words and calls it “rational.”

But his writings, especially when unpacked, echo some of the worst political impulses of the 20th century. His early blogs cite thinkers like Thomas Carlyle, a British reactionary who defended slavery as “natural.” His critique of “unproductive classes” sounds eerily close to 1930s fascist rhetoric about decadence and decline. His flirtation with race science isn’t incidental. It’s foundational. And it’s all hiding behind a wall of irony, academic quotes, and tech jargon.

Writer Quinn Slobodian traces this very genealogy: how the libertarian obsession with markets, when confronted with demands for racial and economic justice, began to embrace biology. How the free-market ideal turned to race realism, IQ fetishism, and “cognitive hierarchy” as ways to explain why redistribution, civil rights, and welfare must fail.

Yarvin is not alone in this lineage. Charles Murray, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Thilo Sarrazin, and others have all tried to give inequality a scientific halo. But Yarvin made it cool, for a certain class of young, male, disillusioned tech nerds who never quite fit into mainstream politics but always wanted to feel smarter than it.

The irony is that while Yarvin decries the “Cathedral” for its supposed groupthink, his own fanbase displays all the signs of ideological capture: disdain for democracy, worship of hierarchy, suspicion of collective welfare, and a yearning for a mythical past where “great men” ruled with clarity and force.

It’s just that now, the “great men” wear Patagonia vests and build space rockets.

But perhaps the most chilling thing about Yarvin’s ascent is how many powerful people find him… amusing.

Elon Musk has quoted Moldbug tweets. Peter Thiel has reportedly invited Yarvin to events and funded institutions influenced by his ideas. The new class of techno-optimists — Balaji Srinivasan, Marc Andreessen, even parts of the “Effective Altruism” crowd — have flirted with post-democratic thought.

You hear it in phrases like “network states,” “exit over voice,” “regulatory arbitrage,” and “sovereign individual.” They all carry the same implicit message: democracy is inefficient, people are irrational, and we need a smarter elite to take over.

These aren’t just fringe tweets anymore. They’re business models. Investment theses. TED Talks.

And that’s the danger. Yarvin’s vision is not being imposed from tanks or coups. It’s seeping in from Silicon Valley whiteboards and startup decks. It’s hiding inside efficiency arguments, waiting to become policy.

It would be easy to ignore Yarvin if he were just another crank. But he’s something worse: a crank with cachet. His ideas have been laundered through podcast interviews, think tank essays, and billionaire VC circles. They’ve moved from 4chan to Substack to Capitol Hill.

And they tap into something real — a growing disillusionment with liberal democracy, especially among people who think of themselves as above it. Smarter than the masses. Rational, not emotional. Deserving of rule.

The truth is, Yarvin isn’t saying anything new. He’s recycling very old ideas in very new language. Monarchism. Eugenics. Social Darwinism. All of it repackaged for a startup pitch.

And maybe that’s what makes it so dystopian. Not that someone believes it, but that someone with a lot of money, power, and code might try to build it.

I came across Yarvin’s world on a forum. What I found wasn’t a political philosophy. It was a product demo for a future I don’t want to live in.

A world where democracy is a glitch. Equality is a lie. And the solution is to hand the reins to men who think coding is governance and governance is coding.

We should take that seriously, not because Curtis Yarvin is correct, but because too many people with power think he might be.