One day, I saw a tweet about Fred Hampton’s death on my timeline—just a quote card: his birth year, his death year, and one of those gut-punching lines that echo in your head long after you scroll past. I don’t remember who posted it or what it said exactly. Something about dying for the people. It had a few thousand likes and an aesthetic background. One of those things that blends into the churn of outrage and inspiration. But I paused.

I did what I usually do: I opened Wikipedia. A ritual now, like flipping open a reference book. Fred Hampton, it said, was the chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party. Assassinated in his bed during a raid by the Chicago police and the FBI. Twenty-one years old. The bare facts landed hard. Then I realized something: the name didn’t ring a bell. Not in the way Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jr. did. I’d never studied him in school, never seen his speeches until that night. So I kept going.

What started as a click turned into a rabbit hole, and what I fell into wasn’t just history. It was a gutting, riveting, utterly American tragedy. But also, a story of power. Of charisma. Of what it means when someone rises from a place they’re not supposed to and starts building something bigger than protest—a real alternative.

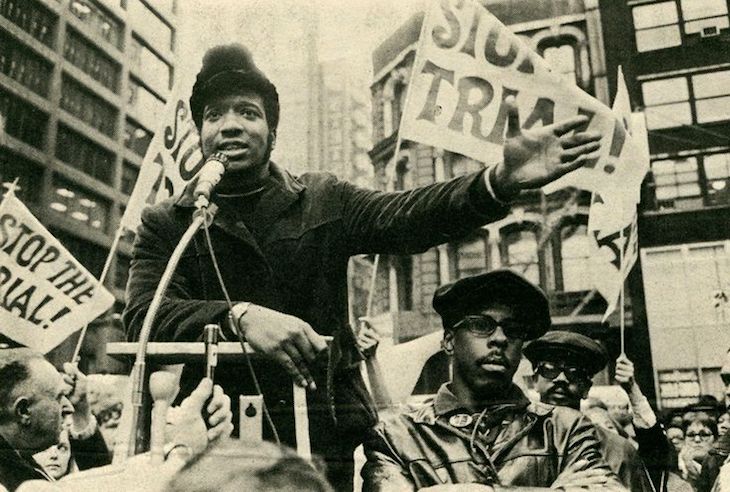

In August 1969, attorney Jeffrey Haas heard Fred Hampton speak for the first time at the People’s Church on Ashland Avenue. Hampton had just been released from prison. The room was packed. Haas describes the moment Hampton took the pulpit like a kind of sonic explosion: chants of “Free Fred Hampton,” the crowd clapping and stomping. No leather jackets, no Panther posturing—just a twenty-year-old in a pullover sweater who stood alone and captured the room.

Hampton started chanting, part preacher, part street poet: “I’m high off the people.” He asked the crowd to repeat after him: “I am… a revolutionary.” And by the eighth round, Haas writes, he was shouting it too. That was the moment. Not a man demanding attention. A man giving it back. Giving it away, and charging people with it like a current. The kind of moment people remember not for the sound, but for how the room felt.

Fred Hampton didn’t rise through elite universities or inherited leadership roles. He was a kid from Maywood, Illinois. Smart, athletic, funny. As a teenager, he organized walkouts in high school over discriminatory policies. He ran free breakfast programs, free health clinics. He read Marx and Fanon and Malcolm X, but he also read people. That’s what terrified the system. He wasn’t just building resistance. He was building infrastructure. Possibility.

He could speak to Black Panthers, to street gangs, to white Appalachian leftists, to Puerto Rican organizers. He called it the Rainbow Coalition before Jesse Jackson ever did. That name was his. And in 1969, when cities were erupting with the rage of systemic neglect, Fred Hampton wasn’t just calling for revolution. He was modeling it. Ground-up. Coalition-based. Armed if necessary, but not for show. For protection.

This wasn’t just theory. He had the community programs to prove it. Hampton helped organize the Panthers’ Free Breakfast for Children Program in Chicago. It wasn’t charity—it was empowerment. The idea was that the government didn’t care whether Black children ate before school, so the community had to take matters into its own hands. It was radical, not because it was violent, but because it was effective.

Parents saw it. Kids felt it. And officials feared it. J. Edgar Hoover, then head of the FBI, specifically called the Free Breakfast Program the “greatest threat” to national security coming from the Panthers. Not guns. Not slogans. But free eggs and toast. Hampton understood what power really looked like—and so did the people trying to contain him.

By the time the FBI began actively targeting Hampton, he had become the number-one person on their “agitator index” in Chicago. His name was explicitly flagged in COINTELPRO documents as someone who could “unify and electrify” the movement. Their words, not mine. So they sent an informant into his chapter. His name was William O’Neal. He became Hampton’s bodyguard. He reported his whereabouts. He drew the floor plan of Hampton’s apartment. He drugged him the night before the raid.

At 4:30 a.m. on December 4, 1969, the Chicago police barged in. They fired nearly a hundred rounds. Fred Hampton was shot in the head, point blank, while he lay drugged and unconscious in bed next to his pregnant fiancée. She heard them say, “He’s barely alive,” and then: “He’s good and dead now.”

None of this is speculative. It came out in trial. Haas, in The Assassination of Fred Hampton, walks through it meticulously. The cover-up, the falsified evidence, the media spin, the eventual legal battle. The police claimed there was a shootout. But ballistics proved only one shot came from inside the apartment. The rest came from the officers. They tried to say the Panthers were violent aggressors. But the facts showed that Hampton and Mark Clark were ambushed.

Haas and his colleagues at the People’s Law Office spent years fighting this case in court. They faced judges who didn’t want to hear it. Juries conditioned to believe law enforcement. But they kept going. They interviewed everyone. They collected documents. They exposed O’Neal. They forced the government to admit what it had done.

In 1982, after a 13-year legal battle, the city of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government paid a settlement of $1.85 million to the survivors and families of Hampton and Clark. No official ever faced criminal charges. No one lost their job. But the truth was out. Hampton was assassinated. By the state. For doing the work the state refused to do.

But what haunted me as I read wasn’t just the murder. It was the afterlife. Or lack of one.

Fred Hampton isn’t on the murals in every American classroom. He doesn’t have a national holiday. You won’t hear his words in TV ads or political speeches by presidential candidates invoking unity. Maybe because unity wasn’t his endpoint. Justice was. Not as a metaphor. As something material: food, housing, education, sovereignty.

His legacy doesn’t fit the feel-good narrative that often gets applied to civil rights history. There’s no I Have a Dream moment. No final speech from a balcony. There’s blood on a mattress. A mother identifying her son’s body. A pregnant woman dragged out of bed. Hampton’s story is too raw, too damning. Too honest.

And yet, there’s something incredibly inspiring about it. Hampton was only 21. In two short years, he accomplished what most political organizers can only dream of. He built alliances, changed lives, redefined what liberation could look like. Not in abstract terms. But in school cafeterias, in church basements, in community clinics.

He took the theory and made it work. He made socialism legible. He made solidarity real. And he did it without ever losing his joy, his fire, or his faith in people.

Reading about Fred Hampton changed the way I think about activism. About power. About who gets remembered and who gets erased. And most of all, about what it means to really be dangerous to the system. Not just because you speak the truth—but because you organize around it.

So yes, I found Fred Hampton on Twitter. But what I found underneath the algorithm was a voice so urgent, so clear, that it still echoes today. And maybe that’s the real reason we don’t hear more about him. Because his vision isn’t finished. It’s still unfolding. In every food pantry. Every mutual aid fund. Every coalition that refuses to be divided.

What also stands out, in hindsight, is how tactical and perceptive Hampton was. He understood the media, understood narrative, and saw how public perception could either shield or expose revolutionary movements. He gave interviews that were sharp and deliberate. He called out the media’s double standards, the way violence by the state was normalized while any Black self-defense was branded terrorism. He knew that representation mattered, but not the kind that sanitized reality. He wanted the truth—in all its rage and complexity—to be visible.

And the more I learned about him, the more I began to question why our education system treats certain leaders as safe and others as dangerous. Why we’re taught to memorize King’s dream but not his demand for economic justice. Why we don’t know Hampton’s name, even though his work touched every intersection of justice we still struggle with today. Healthcare. Policing. Food access. Housing. Coalition-building. Fred Hampton didn’t just show up for the revolution. He tried to design its infrastructure.

We live in a time when grassroots organizing is again under surveillance, when protest is again criminalized, when poor communities are told to wait their turn. Hampton’s story is a reminder that waiting has never been how change happens. It’s built, usually by the very people who are told they don’t belong at the table. Hampton didn’t wait for permission. He showed up with a chair. And sometimes, a bullhorn.

As Hampton once said: “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution.”

And maybe you can’t kill the truth either. But you sure can bury it. Until someone goes looking.